A dear friend who also self-described as my “favorite troublemaker” recently wanted to hear my thoughts on “balanced training.” I thought that was a little bit hilarious because she knows perfectly well how I feel about punishment-based training, generally speaking (and yes, I know that so-called balanced training isn’t just based on punishment, but it does feature consistently and/or often). But in light of some recent conversations and internal philosophical musings, I’ve decided to expound my views. This post is far from the be-all-end-all of my thoughts on balanced training or punishment in general, but it’s a start. If there are particular parts of this you, dear reader, would like to discuss, I am happy to engage in a respectful, compassionate dialogue. If you just want to hear more about what I think, I can certainly elaborate on anything, too.

When I started learning how to train dogs at the East Bay SPCA in Oakland back in the early aughts, I was trained not only how to use a clicker and deliver treats at the appropriate time, but also how to use a choke chain. We didn’t actually put them on the dogs, we placed them on a chain link fence so we could practice “pop corrections” without actually inflicting pain or discomfort on a real dog. I never in fact used a choke chain while I worked there, but it was part of my education because I was told that I needed to learn how to use all the tools. All the tools. This was at a time when shock and so-called “e collars” were not nearly as popular or prevalent in the training world, at least not for pet dogs. The philosophy that that we worked under, at that shelter, at that time, was, we use what works for the dog.

There was one dog from my time there who seemed to be fairly uncontrollable–a large fluffy German Shepard mix named Pellinore. After trying standard treat-based training methods the decision was made by leadership to try a pinch collar on him to reduce his jumpy/mouthy behaviors to the point where he would be considered “adoptable”. He wore that for a very brief period of time before he was transitioned to a head collar, but the fact remained that we, the training staff at an animal shelter, placed a dog on a punishment device intentionally.

In hindsight I feel that the reason a pinch collar was chosen and utilized was because the skill level and education of the handlers and decision makers, myself included, was not nearly where it should have been to create a force-free plan for this dog at that time. Everyone was doing the best they could with what they had, and no one had any ill intent. The dog certainly was not irreparably harmed (to my knowledge) by the use of this tool, and he ended up in a wonderful home with a family who loved him very much and renamed him “Wookie”. From my perspective now, with well over a decade of education and hands-on experience behind me, it wasn’t the right choice to use that pinch collar, but it was something that probably would have been used by a “balanced trainer”. Now I think we could have done him better.

Folks who call themselves balanced trainers, to the best of my understanding, are trainers who utilize a combination of punishment techniques as well as reinforcements. Things that fall into the punishment category include corrections with choke, pinch, slip, or similar collars, verbal reprimands, and/or shocks from electronic collars. Those aversives, used to reduce undesirable behaviors are “balanced” by the use of various reinforcers such as treats, praise, play, access to toys, and so on, which are used to increase the likelihood of desired behaviors.

The deep dark dirty secret of behavior and behaviorism is that punishment works. There have been studies upon studies upon studies on all kinds of species, including human children, that show that punishing behaviors through use of applying aversive stimuli is an effective method for behavioral change, and often a fairly fast one (though it should be noted that speed of efficacy is typically based on severity of the aversive; i.e. level of pain or fear [of pain] inflicted). There are of course caveats to this – you can google “punishment doesn’t work” and read a plethora of articles on the ineffectiveness of punishment in dog training, criminal justice systems, classrooms, and so on. That said, there are also plenty of other studies as well as endless anecdotal reports from dog owners, professional trainers, not to mention the sales data for electronic collars and invisible fences that speak otherwise.

Let’s take it as a fact that some types and applications of punishment do in fact work to train a dog to do or not do a variety of things. If this is the case, why on earth are so many dog trainers and behaviorists opposed to using effective methods, even just sometimes?

In short, because there’s a better way.

Let’s say you have two options in front of you to modify your dog’s external behavior (what he is doing with his body):

One option is shorter in duration, but would certainly cause your dog stress, fear, discomfort and/or pain, and would very likely do nothing at all to modify his internal processes (emotional responses, state of physiological stress) for the better; it may even make it worse. There is little time, effort, or energy lost for the person.

The other option is slower, requires significant accommodation for the dog, but is most certainly not going to cause pain, and if any stress or fear elicited it is minimal to the point of not causing a pronounced behavioral (external) response. The aim of this option is to specifically change the dog’s internal processes to reduce unpleasant emotions and maintain physiological stasis while achieving the desired behavioral result. It requires more time, patience, energy, and commitment from the human.

Both these methods work, but the big difference to me isn’t simply how they work, but who they are working for. Option one (punishment, obvi) works for the human. There’s no major impact on the person’s life, they don’t have to change much at all, and they will see (external) results in a reasonable period of time. It should however be pretty damn obvious that this method is basically crap for the dog, as it becomes up to them to learn what’s desired of them, or else.

For people who do not recognize (or care?) that dogs experience emotions, including fear, joy, frustration, and anxiety as well as experience stress and all it’s physiological consequences in ways shockingly similar to humans, for those people I can see how they justify the use of positive punishment* methods in fairly pedestrian situations: jumping on guests, barking at delivery personnel, pulling towards other dogs on leash, and so on. And I can also see “balanced” trainers feeling okay with using punishment knowing that they would still be doling out the praise and/or treats for tasks accomplished well.

But let’s look at option two:

Option two has little negative impact on the dog, but requires comparatively quite a bit from the human. The responsibility for behavioral change is in the hands of the person to make sure that the dog is set up to learn without stress (which, for the record inhibits learning – you can Google that one yourself). In many cases this method requires huge shifts in how we live and work with our dogs, and therefor requires the pet parent to be willing to make sacrifices for the sake of their dog’s well-being.

That’s asking a lot, but I don’t think it’s asking too much. If you think that sounds like too much, let’s read the descriptions of the two options again, but replace the word “dog” with “child”.

One option is shorter in duration, but would certainly cause your child stress, fear, discomfort and/or pain, and would very likely do nothing at all to modify his or her internal processes (emotional responses, state of physiological stress) for the better; it may even make it worse. There is little time, effort, or energy lost for the parent.

The other option is slower, requires significant accommodation for the child, but is most certainly not going to cause pain, and if any stress or fear elicited it is minimal to the point of not causing a pronounced behavioral (external) response. The aim of this option is to specifically change the child’s internal processes to reduce unpleasant emotions and maintain physiological stasis. It requires more time, patience, energy,, and commitment from the parent.

Suddenly seems a little more obvious which method to choose, doesn’t it?

No, dogs are not children, but there are a lot of clear parallels, the most relevant being: adult humans are responsible for looking out for both children and dogs’ mental, physical and emotional well being and best interests as they cannot sufficiently advocate or care for themselves.

For the most part, people now agree that you can raise children without hitting or yelling at them, but for some reason, a large number of folks still think you “need” pain or fear to train dogs. That’s just one of the many falsehoods that trainers who emphasize punishment in their protocols are holding on to: it justifies their methods. In addition to the “punishment = good” (or at least “useful” or “necessary”) half for the story, there are also misconceptions spread about what positive reinforcement training is, allows for, and both how and why it works.**

The claim is made by many self described balanced trainers that positive reinforcement (R+) or force-free dog trainers believe in “never saying ‘no'” or let problematic behaviors go ignored without interruption. This is far from actuate. Most, if not all, R+ trainer use some methods of punishment, some of the time, because technically just turning your back on a jumping dog can be a punishment, or using a head collar for an anti-pulling walking device.

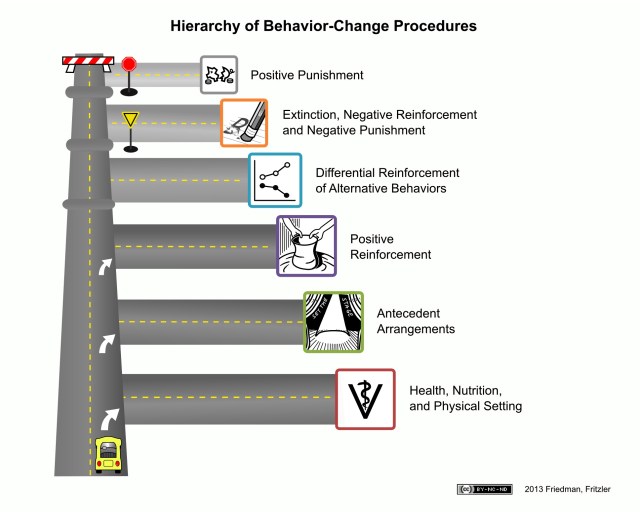

For the most part, well educated and skilled R+ trainers follow what’s known as The Humane Hierarchy when working to resolve training or behavior concerns. The Humane Hierarchy is A Big Deal, and it’s awesome. It is a road map to addressing issues by starting with the Least Intrusive, Minimally Aversive (LIMA) methods, and as one method is exhausted, then move on to the next least intrusive/minimally aversive method. The Hierarchy places the animals’ well-being front and center because, again, they can’t advocate for themselves, so we have to take their welfare not only into account, but make it the most relevant thing in a training plan, right up there with efficacy.

You can see from looking at the graphic below that use of positive punishment (adding an aversive consequence) is on the list of options, but as a last resort. That means, if you’ve tried and exhaused everything else and your options are now re-homing/euthanizing the dog or using a punishment based method, maybe it’s worth trying.

The problem arises with the phrase “tried everything else”, because most of the time “everything else” hasn’t been tried, or at least has not been correctly/sufficiently/appropriately to say that method is exhausted.

Most balanced trainers do not follow the Humane Hierarchy roadmap or operate under the guidelines of LIMA. Maybe there are some who do, but when LIMA & the HH are in place, you almost never get to the point to need positive punishment because all those other methods work, and work well. The use of positive punishment is reserved for seriously extenuating circumstances, not because it’s easier for the human to press a button or jerk a leash than modify their own behavior, because, again, we are our dogs’ only advocates: it is our responsibility to care for them: physically, mentally, emotionally. They can’t do that for themselves.

The Humane Hierarchy places methodology on a scale to be balanced against the animal’s emotional and physical well-being, which gets the most weight, always.†

There will be times that circumstances are extenuating, or certain methods not accessible. For example: if we have a dog who continues to escape his yard, scaling over even a 7′ solid wooden fence, and the possible repercussions of those escapes include getting hit by a car or killing a neighbor’s cat, would it be okay to put in an invisible fence? What are the other options? Let’s assume for the sake of argument that the dog is receiving age-appropriate exercise and enrichment, a tie out or runner have been tried in the past but the dog has managed to get dangerously tangled, and it is unrealistic for the dog to be attended/babysat every time he’s in the yard†† for what would likely be the duration of the learning process, which removes most of the training options. If it boiled down to getting rid of the dog or using an invisible fence, which would you choose?

Is it better for the dog to be sent to a shelter (to potentially be euthanized for untreatable escape behavior) or placed with another family who will still have to deal with this problem (it’s not like changing homes will make the fence jumping behavior magically go away), or for him to stay with the family that knows him and loves him, but to experience the discomfort/pain of an electric shock as many times as it takes for him to learn the boundaries of his yard? Knowing that invisible fences are not guarantees and many dogs push through the shock to get to the outside world, is it worth trying?

In this case, IF we have made it though all those other options on the Hierarchy and eliminated them as either “tried correctly and completely” or “not available”, then I say, give the invisible fence a shot.

After saying that I still maintain that I am a force-free and R+ trainer, because this is the only option left on the scale that balances against the dog’s physical and emotional well-being as training with a shock collar in my opinion is in this case preferable to death.

You see what I did there? I’m still advocating for the dog’s welfare.

This is an extreme hypothetical case, but not too unrealistic. It is one of the rare, rare times when all other options have truly been exhausted in one way or another and we’re left at that last turn-off on the Hierarchy map before we hit the dead end.

Most training and behavior concerns don’t have to go all the way to that last turn off. A well educated and proficient R+ trainer can get satisfactory resolution out of nearly every issue prior to hitting that positive punishment turn-off, and we choose to do so because it’s fairest to the dog. It might take more work, commitment, and ownership of the issue from the person, but you know who’s job it is to care for that animal? The person.

Let’s sing it from the rooftops: we are our dogs’ advocates. With that fact clear as a bell, we are doing a disservice to our voiceless animals to cause stress, pain, or fear when there is another option available, and that other option is, with only very rare exceptions, always available.

So, balanced training?

I’m happy balancing the dog’s very real needs with an effective training plan, and so far use of positive punishment hasn’t needed to come into the conversation.

*Positive here does NOT mean “good” it means that the punishment is added, as in: when the dog behaves undesirably, an aversive consequence (shock, pinch, etc) is added/applied: Dog barks + electric shock = less barking. For more on the terminology of operant conditioning, check this info-graphic out.

**I want to make clear here that I do not believe that the trainers who espouse these views are inherently bad people or intentionally spreading untruths. I think, that similar to my history at the East Bay SPCA way back when (they have changed since then!), they are truly doing what the think is best given the tools and education they have.

†I would love, more than anything to reclaim the term “balanced training” to mean that all training methods used are placed on this scale – that any trainer who calls themselves “balanced” is implying that they are weighing everything they chose to do against what’s best for and fair to the dog. Not gonna happen, but a girl can dream!

†† If you’re having a hard time imagining why it would be impossible or unrealistic to stay out with the dog every time he needs to use the yard, imagine a single parent with one or more kids under the age of 10. The dog can not reasonably command 100% of that person’s attention every time he needs to potty.